She brought down Juho’s journals from the shelves in her room to reread them – with the light of his secret message, and the understanding of Correb’s distortion, it gave new meaning to large sections of his book.

‘No wonder he secludes himself – he is not well’, made her pause, and look for more. She found a brief paragraph:

He lays on his seat, by the windows that face the forest, next to the water feature, and he rests. We exchange no words. I keep working and he closes his eyes - as a ferryman, he does not sleep.

I do not know why he finds the greenhouse more comforting than his own tower, but he is not in my way so I’m not annoyed by his presence. He likes to be there at night, when most of the guiles are sleeping and won’t pass by and see him.

Recently, he seems too ill to make it to the greenhouse. I have not seen him in his usual spot in weeks.

He has returned to the greenhouse. I do not need to ask anything to know he has had a worse spell.

Moth was not sure whether the ferryman’s sickness was his distortion, or if he was both sick and distorted. She assumed it was the latter.

Does it change anything? She wondered, looking down at her hands. Even if I knew he was monstrous, I still had no choice, I still had to go through the water.

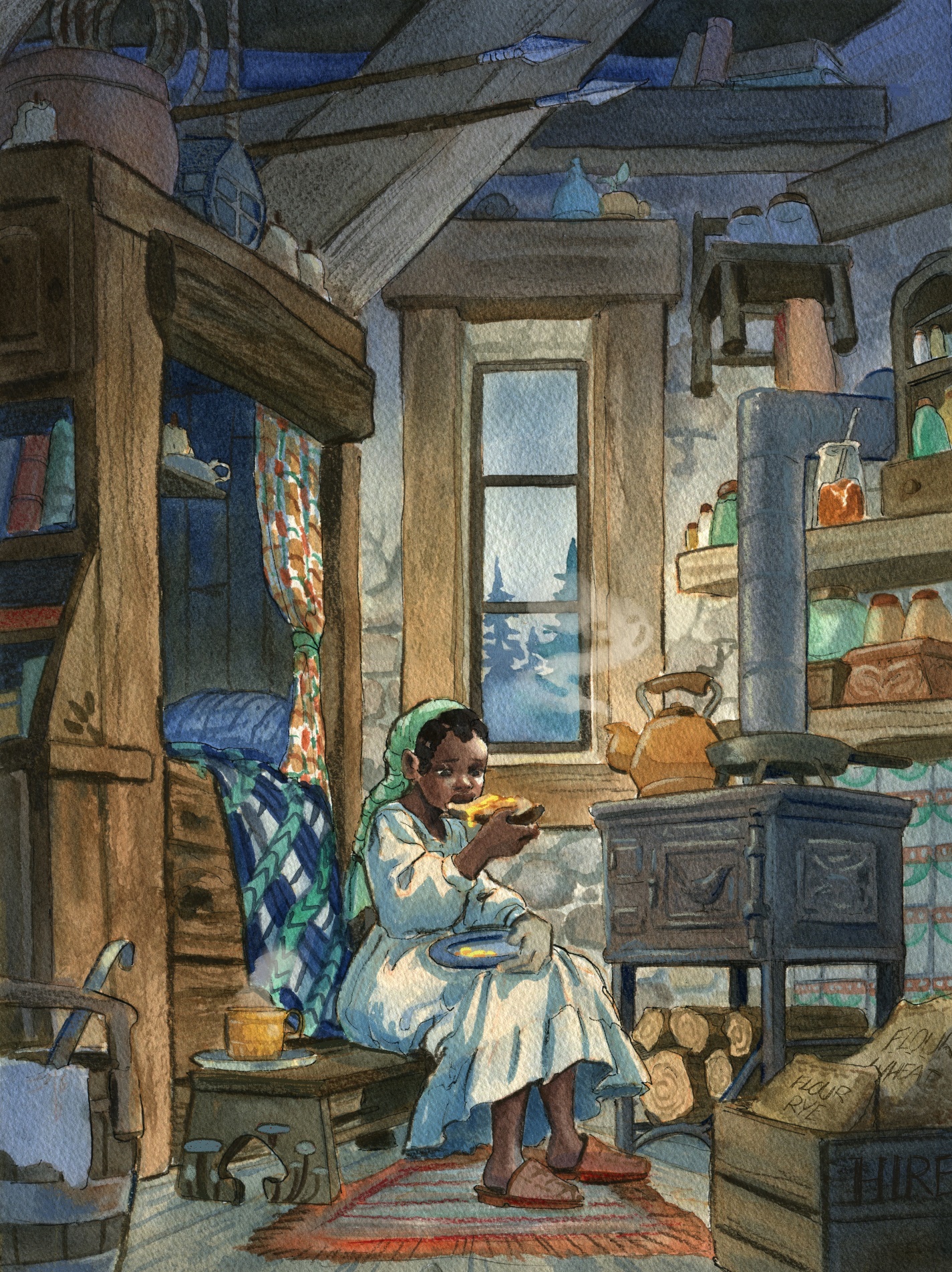

She did not understand the numbing fear that came over her. She paced around her room, one hand holding the book, the other hand clutching her hot, churning stomach. She had a feeling like she was never going to see her family again.

Sick and anxious, she got a pencil and wrote in her own journal a letter to them.

I may never see you again. The Ferryman is sick – but he is alive. He has been severely distorted by a curse and does not want to be seen by anyone.

She could think of nothing else to write. Someone needed to know – she understood that Correb kept it secret, but if she died, no living person would know – if anyone should know, it was Clem. She ripped the little note out of the journal.

Moth hurried to the window of her room. Magpies often gathered on little awning that faced the forest. She opened the window and leaned out, spotting a few hopping around on the edge.

“Hello?” Moth asked, and they cawed back at her. “Would one of you send this out for me?”

One of them hopped forward, tilting its head. “Come in, it’s getting dark?” it asked.

“Yes, yes, to my mother Vade,” said Moth, desperate. She lifted her scrap of paper. “Would you send this letter to her, I–”

The magpie jumped back from her, glaring at the paper.

“No haunting,” it cawed.

Lowering her hand, Moth asked, “What?”

All three magpies said in a raspy chorus, “No haunting.”

“I can’t send written things?” Moth whispered.

They nodded their heads.

Crumpling the note, Moth flung in into the stove, where it curled into ash.

Moth lay on her bed, exhausted. There was nothing to do but wait for him; tomorrow, he would be back.

What will you say to the ferryman when you stand face to face with him?