Chapter 24:

Correb’s Blessing

After breakfast, Mrs, Tunhofe hitched Kakara – her old nag – up to a cart, packed a large lunch, and set out down the road with Moth next to her on the box seat.

Moth borrowed a wide hat from Rodin, and a sturdy apron from Priscilla, and Mrs. Tunhofe had given her an empty journal and a pencil. She felt ready.

“First farm I’m heading towards is South-East, past Ren’s Corner, to a family called Halig. They’re out of the way, they don’t farm large-scale, keep to themselves and their own – you’ll find there’s a lot of farmers who sit on the edge of the region and don’t talk to anyone, much.”

Moth wrote down the date, the location, and the name of the family.

It was indeed out of the way, as they drove for over four hours through a warm spring day, with no clouds for cover, but a merciful breeze pushing behind them further to the edge of Hiren.

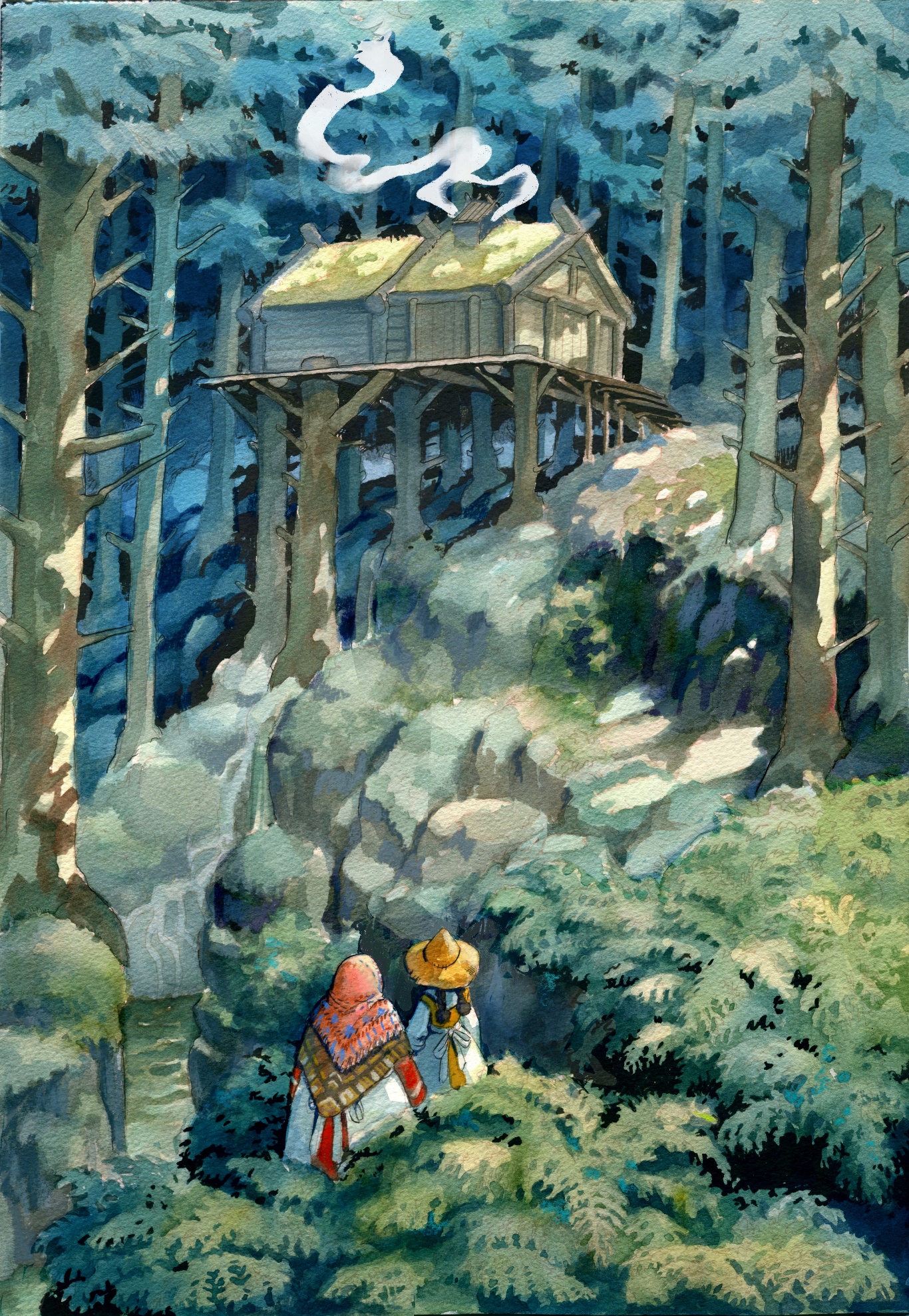

Tiding Range loomed closer and closer, trees clustered thicker together as farms disappeared, the ground rocky and uncultured, and the prairie grass high enough to annoy Kakara. She whinnied, plodding through the dense undergrowth.

Moth had never been this close to Tiding Range before. It had scared her as a child – made her anxious as an adult - and it was too far a distance to comfortably travel to just for fun; on top of which, she was concerned she’d meet a worshipper, bloody and violent on the mountain.