Chapter 26:

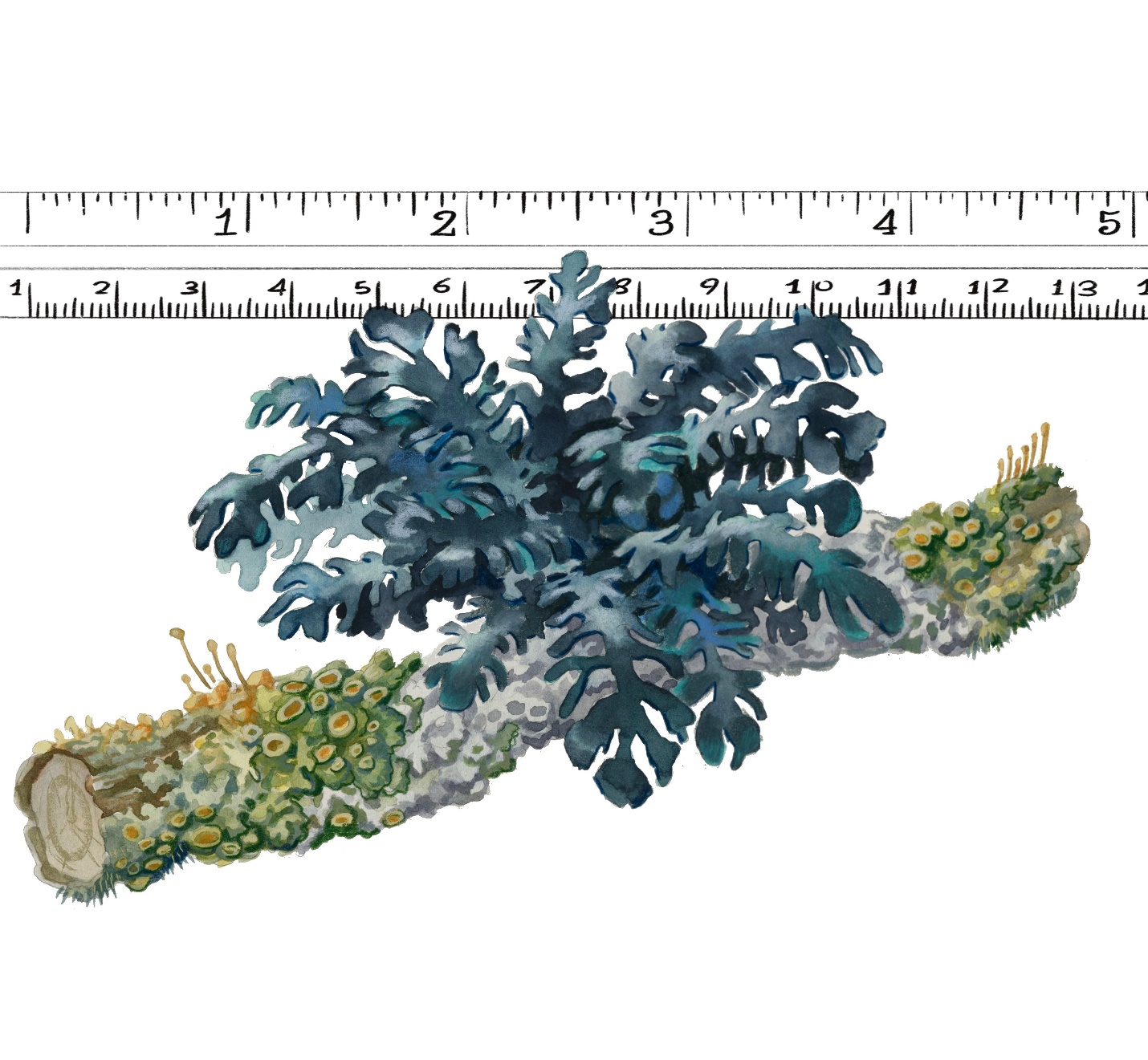

Mapmoss

When they reached the main house, Ama ran to their mother for archery lessons, and Moth went inside through the kitchen and into the small bedroom room next to the parlor, where Grandpa Clem often sat at the window by his desk.

“Moth!” he said, looking up from the letter he was writing. He reached out his arms, and Moth sat on the arm of the chair and hugged him tightly. “How’s the journaling going?”

Moth pulled out her journal, grinning. “This is the account of ten different families; none have written to you – or anyone – about the fog.”

Clem fumbled for his glasses and took the journal gently in his hands. He looked down at it and closed his eyes for a moment, gave a deep sigh, and opened it carefully. “Oh, you’re handwriting is so clear – this’ll be a delight to read.”

“I’ll make some tea and come watch you.”

“You’re going to watch me read? Were there no thrills in Magden you had to come all the way to me?”

Moth hurried to the door. “Don’t start until I come back.”

After she had made a tray of tea and some cut up fruit with cream, Moth returned to Clem’s room and sat on the windowsill and nodded to him.

He opened the journal with his frail hands and began to slowly pour over the words – soon he forgot Moth was even in the room, he bowed over the journal as if in prayer. Now and then, he’d reach to the side where he had rows and rows of letters