Chapter 46:

Memories in the Mud

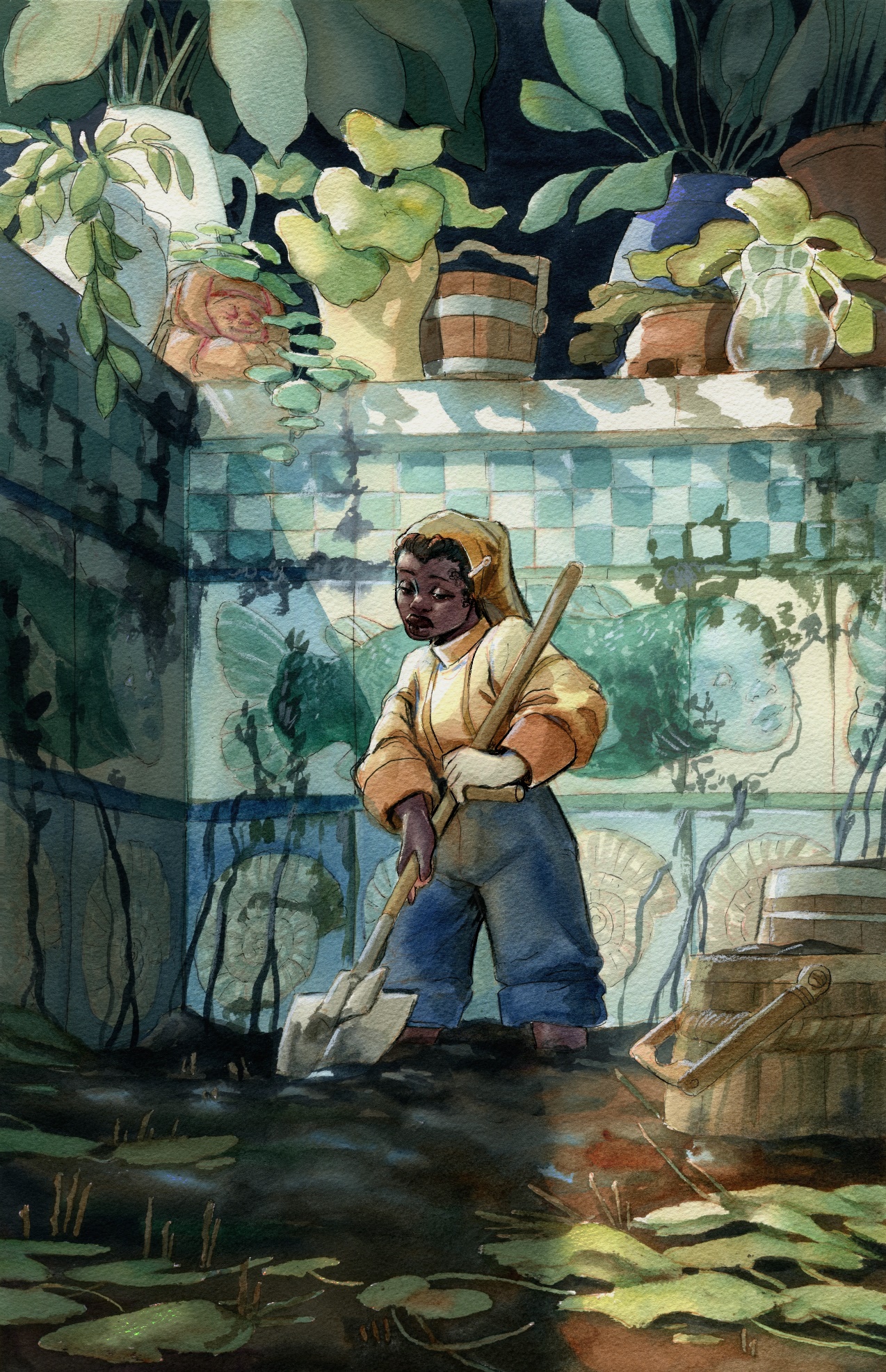

Moth didn’t want to go back to the greenhouse.

Unsettled and unable to give language to her heart, she dreaded working in the greenhouse under Correb’s observant eye – she dreaded any questions he might ask, or any conversation he’d strike up.

Moth wanted to avoid him altogether, but knew it’d be impossible, considering she’d agreed to listen to him read again at noon, and she didn’t have the courage to snub a ferrier. She decided to enter the greenhouse early and silence her exasperated emotions with work.

The day had only just begun when Moth crept into the greenhouse. It was still, and dark, and Lord Correb was not there – Moth sighed, feeling weightless, and walked around the greenhouse easier knowing she was alone.

Today, she would muck out the pool.

She had borrowed clothes from Lander – to avoid a conversation entirely with Agate about the propriety of a Lady doing this or wearing that. Those corrections were beginning to exhaust Moth, and she realized guiltily she avoided Agate now. Lander’s clothes were large on her but she rolled and re-rolled the sleeves and pants, and forwent shoes altogether.

Moth brought over every bucket she could find, set up a pulley, and lowered a ladder into the pool.